More Questions Sent to the Judo Information SiteQ How should I wash my Gi? A Wash the jacket and pants in cold water. Cold water will remove blood stains and hot water will set them. Avoid the use of bleach, as bleach will eat into the fabric and weaken it. Drip dry for longer wear. Hot tumble drying will make the fabric softer, but the tumbling in the dryer will fray the fabric over time. 100% cotton will shrink in hot water or use of a dryer. Do not wash the belt, and be sure to tie the ends of the strings on the pants.

A Washing in cold water should prevent bleeding. Of course wash colors separately, blue with blue and white with white, and ensure that all soap is rinsed out thoroughly since any residue can cause the blue to bleed. Although I have not tested these instructions, here are the washing instructions you may have heard of for a reversible or blue gi:

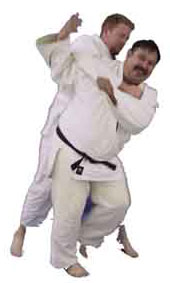

Q I have worked out with a couple of judo clubs and have very much enjoyed it, especially the matwork. However, taking ukemi from a throw has almost always given me bad headaches, and, as you might imagine, has caused me to develop a fear of being thrown. Do you have any advice regarding my problem? A You did not say how long you have been practicing or how old you are, but fear is very natural. Headaches would possibly indicate a jarring that is excessive, or it could be caused by the loss of orientation (like doing a lot of rolls), or even fatigue, stress or tension. I will assume that the mats are adequate, and you are being thrown correctly and with control. There are many different ways to practice ukemi in class to prepare you for falling from throws, and this is the primary method we use to help avoid injury and fear. We also use easy, controlled throws with beginners to give them real life practice before throwing in randori. So the answer is to take small steps to build up your falling skills and your ability to relax. Being fearful only makes the falls worse, and the way to overcome this is to go back to the basics until they are mastered and your confidence returns. For more information see the articles on Ukemi, Falling and Relaxation. Q I am a 3rd KYU Judoka and on my syllabus there are two throw variations for 2nd KYU that i can not find anywhere either on the net or in any book. They are O-Uchi-Mata, Major inner Thigh, and Takai Uchi Mata, which i don’t know, could you help? A I didn’t know the answer but found the following information in the Masterclass Series book Uchimata by Hitoshi Sugai (page 12): While uchi mata may not have been part of Jigoro Kano’s Judo until the turn of the century, it certainly did exist in the secret scrolls of other schools, including those of the Te Koku Shobu Kai, a jujitsu school in the Kouki Ryu tradition, which claimed to teach members of the Tokugawa family, the former ruling family of Japan. In 1911 to the Te Koku Shobu Kai published in book form its secret teachings. The school identified three forms of uchi mata. These were ko uchi mata, taka uchimata, and o uchimata. Though the text is none too clear, it seems that these corresponded to the three placings of the lifting leg as follows:

Q Often the samurai are described as strong individuals and admired. Hovewer there is one thing about the samurai that I find destructive. And that is hara-kiri. I suppose they did not kill themselves because that they did not want to live, but to reason of restore honor when they had lost honor and similar things. I would like someone who can explain to me that budo and judo do not support these ideas. That budo and judo teaches to live as long as you can and enrich life, and to contribute with a little good to society. Am I right? A I have never seen anything recorded directly from Jigoro Kano about this question of suicide. However, I think your interpretation of his general philosophy is correct and he would view it as negative, irrational, unnatural and unnecessary. Hara kiri (or seppuku) developed as an intregal part of the code of bushido and the discipline of the samurai warrior class. The early history of Japan reveals quite clearly that the Japanese were far more interested in living the good life than in dying a painful death. It was not until well after the introduction of Buddhism, with its theme of the transitory nature of life and the glory of death, that such a development became possible. The spirit of Zen Buddhism in particular cultivated among its warrior followers an attitude of going forward with whatever rational or irrational conclusion a man has arrived at. At the same time there was an absence of Zen teaching about the immortality of the soul, righteousness, or the divine way of ethical conduct, all factors that influence the western mind. To the samurai, seppuku–whether ordered as punishment or chosen in preference to a dishonorable death at the hands of an enemy–was an unquestionable demonstration of their honor, courage, loyalty, and moral character, all more important concepts in the code of bushido than preservation of life. Honor for the samurai was dearer than life and in many cases, self destruction was regarded not simply as right, but as the only right course. Disgrace and defeat were atoned by committing hara-kiri or seppuku. Upon the death of a daimyo loyal followers might show their grief and affection for their master by it. Other reasons a samurai committed seppuku were: to show contempt for an enemy, to protest against injustice, as a means to get their lord to reconsider an unwise or unworthy action, and as a means to save others. It is important to note that not all Japanese samurai or lords believed in seppuku, even though many of them followed the custom. The great Ieyasu Tokugawa, who founded Japan’s last great Shogunate dynasty in 1603, eventually issued an edict forbidding hara-kiri to both secondary and primary retainers. The custom was so deeply entrenched, however, that it continued, and in 1663, at the urging of Lord Nobutsuna Matsudaira of Izu, the shogunate government issued another, stronger edict, prohibiting ritual suicide. This was followed up by very stern punishment for any lord who allowed any of his followers to commit harakiri or seppuku. Still the practice continued throughout the long Tokugawa reign, but it declined considerably as time went by. It was both outlawed and viewed unfavorably by the time Jigoro Kano was born and bushido was in decline. To die isagi-yoku is one of the thoughts dear to the Japanese heart, even in modern Japan. Isagi-yoku means leaving no regrets, with a clear conscience, like a brave man, with no reluctance, or in full possession of mind. The Japanese hate to see death met irresolutely and lingeringly, and some are therefore prepared to sacrifice their lives for any cause they think worthy. While there are unquestionable zen, samurai, and Japanese cultural influences in Judo philosophy these particular attitudes towards suicide were not retained. This is one of the many respects in which Jigoro Kano updated the old bujutsu practices. Of course at first Judo dealt only with the techniques and basic principles. The more esoteric philosophy of Judo was not developed until the 20th century when even Japanese society had changed considerably from feudal times. Judo does deal with life and death. The study of attack and defense helps one understand and face death bravely. But suicide is rather seen as an abnormality. I think Judo recognizes our innate and unconscious desire for life, and it is this what we strengthen through Judo practice. We strive to see death and defeat realistically so that we can maintain high moral principles and meet danger without a second thought when necessary, but this is a far cry from putting oneself into harm’s way intentionally or taking one’s own life. Hara kiri ultimately was a feudal practice that was glorified beyond its importance in society, partly because of its unique Japanese character. It has had lasting influence on the Japanese psyche, accounting for the practice continuing to this day, but it is not accepted in most cultures and has nothing to do with Judo. Send your questions to . |

| The Judo pupil, therefore, must cultivate his mind; he must never feel fear, never lose his temper, never be off his guard; but he must be cool and calm, though not absent-minded; he must act as quick as thought, according to circumstances. He must also be dexterous as well as bold both in attack and in defense. –Sakujiro Yokoyama and Eisuke Oshima |  |

Q

Q