by Donn F. DraegerPART 1: NAGE NO KATA and KATAME NO KATA Donn F. Draeger is well qualified to write about this subject. A scholar of oriental history and philosophy, he has done considerable academic and practical research on the oriental martial arts; and as a jujitsu historian, Mr. Draeger is currently engaged in kata research, including the major fighting arts of Japan. As an instructor in the Kodokan’s foreign section, he has specialized in the study and teaching of Kodokan Judo kata. He is the only foreigner to have been awarded the official kata teaching licenses by Kodokan, holding licenses in six of the seven recognized kata. His knowledge and skill are attested to by the decision of the All-Japan Judo Federation to permit him to become the first foreigner to perform nage no kata (as tori) at an All-Japan National Judo Championship (1961). He was further selected by the Kodokan to be the first foreigner permitted to perform high-grade kata (uke for goshin jutsu and kime no kata) at the annual Kagami Biraki ceremony in 1963 and 1965 respectively. He was again nominated by the All-Japan Judo Federation to perform nage no kata (as tori) at the 1964 Olympiad — the only foreigner accorded this honor. …..Editor Kata? Not in this dojo. We only do fightin’ Judo here. It’s bad enough you have to learn some of it just before ya’ wanna pass your Dan exam; but after that…..forget it! The intent and meaning of these and similar opinions about kata having rung out in scores of dojos throughout the country. Unfortunately, it has been relatively easy for a novice judoist to overhear such opinions; and it is still easier for the novice to condition his training by the blind acceptance of such poor advice. All of us, without exception, have at one time or another harbored such misconceptions about kata. This is due principally to two reasons. First, it is a natural consequence of our lack of familiarity with the intended wholeness of Judo. This natural consequence, in itself, cannot be condemned; but as a prevailing attitude, it becomes an evil which adversely affects the maturation of one’s Judo. Secondly, the truth about kata, its intent and purpose as well as training applications, is generally unavailable. It is only through correct Judo education that one may come to understand and appreciate the importance of kata and apply it intelligently to his training and secure it benefits. Unfortunately, this article cannot give you specific technical advice or discussions about kata because of the space limitations. Such information, correctly written, would require a comprehensive book. It may be more important and appropriate to simply convince you of the importance of kata. This article, therefore, will deal with a “sales talk” about kata, with the hope that it will provoke and “awaken” you to discover the technical truth about it and bring new, vital life to your training. If it can accomplish this, you will reap many benefits. What is referred to as kata applies in principle to all kata. But for the purpose of this article, the interpretation of kata refers to the nage and katame no kata. Since you are expecting a “sales talk,” it may be best to start with something practical about kata. Just who in the Judo world uses kata? Speaking on a top-level international basis, you should first know that there aren’t any champions who cannot perform kata; all champions perform it well. While kata alone has not made them champions, the very fact that they can do it expertly means that somewhere along their long, hard training road they have employed it in their training. Their expertise with kata did not come by a process of osmosis. In terms with which you are at least geographically familiar, few of you will disagree that the competitive style and effect of, say James Bregman is currently the most dynamic and is the best in the USA. Bregman’s Judo history and contest record dates back many years; but he may be best known to you as the 1964 National AAU Middleweight champion, the 1964 Olympiad Middleweight 3rd place winner, the 1965 Maccabiah Games Middleweight champion. Having had a large share in Bregman’s early years of Judo training, personally designing and directing all of his training schedules during those formative years, I can assure you that he literally “grew up” on large doses of throwing and grappling kata, the nage and katame no kata respectively. Another national case in point lies with the current National AAU Grand Champion, Hayward Nishioka (Nanka), who also exhibits a tremendously effective and stylish Judo which is outstanding among American Judoists. Nishioka’s skill with kata is also remarkable; and, together with Bregman, they were chosen by the All-Japan Judo Federation to perform nage no kata at the 1962 All-Japan National Championship – the second foreigners accorded this honor. Their splendid performance is well remembered in Japan. Past champions in our national Judo scene include Ben Campbell (Hokka) and, further back, John Osako (Konan). Campbell will be remembered for National AAU weight titles and Pan American titles, and Osako for AAU Grand National Championships and two Pan American Grand Championships. Both of these competitors possess excellent skills with kata. Currently aboard — starting with World and Olympic champion Anton Geesink of the Netherlands down through such famous champions as Japan’s winning Olympic trio Iasso Inokuma, I. Okano, and Nakatani, as well as Japan’s three-time all-Japan champion A. Kaminaga and the currently reigning All-Japan titlist S. Sakaguchi, Canada’s Douglas Rogers, and A. Kiknadze of the USSR — all are, without exception, kata experts. As a sidenote of interest, All-Japan championships on a truly national basis began in 1948; all winners — two of whom have been world champions — were and are kata experts. European past international “greats” who were and still masters with kata include France’s B. Pariset and H. Courtine; Belgium’s H. Outlet; and Great Britian’s C. Palmer, G. Gleeson, and G. Keer. So much for who does kata in expert fashion; let’s see what kata is. Finding out what kata really is, its purposes, and how to employ it in training is not as easy as you might imagine. But one fact is sure; merely turning to the average daily Judo scene for this information will not produce the answer. Kata as practiced today (perhaps with rare exception) is not the kata intended by the founder, Jigoro Kano, and is not giving optimum benefit to Judoists who perform it. Just why this is a fact requires some discussion. In my own experience, as I saw more and more kata, I knew that something was amiss; just what that “something” was, however, eluded me. All I could see — and what you too will see if you take time to look around — was a meaningless, arid “dance of shadows” in each kata performance. Largely, kata was an exhibition; there was no modern-day training application for it. I became suspicious and immensely intrigued; for, knowing full well the practical and efficient mind of Jigoro Kano, the designer of Kodokan Judo, I knew that he would not give kata such weak intention. Kata for him must have had an efficient function and a definite role to play for judo. I began with a comprehensive survey of all Judo books published. Every major work on kata ever published, including those in Japanese language, was included. They brought absolutely little or no help for, at best, they are all incomplete, being filled with technical gaps that leave many major issues unanswered. The only exception, in my opinion, was found in the two works of T.P Leggett, The Demonstration of Throws and the Demonstration of Holds, and one Japanese classic. While giving thorough technical details, they however lacked the practical application of kata to training. Still perplexed, I fell upon the idea of interviewing the oldest and most experienced sensei I could find in Japan. Surely, if this information was unrecorded, it must be in the minds of the oldsters. I was only partially right in this thought. In the interviews, all sensei spoke of modern-day kata as being far off the track. They pointed out technical discrepancies on the current mat-scene which convinced me more than ever that the real truth about kata was not getting out to the modern Judoist, not even from those who knew. The reasons for this apparent laxness will not be discussed in this article. It is sufficient for our purpose to know that it is fact. In one of my interviews I had the good fortune to meet with the former secretary of Jigoro Kano, who told me that I would find interesting and complete information on kata among the founder’s personal technical notes and diaries. These sources, plus the classic work on kata written by Yamashita and Nagaoka (now out of print) and edited by Jigoro Kano himself, were filled with the original concepts of kata. Since he was in possession of those documents, he offered to let me peruse them. I jumped at the chance and found exactly what I had been looking for all these years. I want now to pass on to you some of the information that I discovered, limiting it for the sake of brevity to discussions other than pertinent to specific techniques. First of all, the great fighting systems of Japan, the bugei, were made effective and were actually constructed from kata. Whether systems of “empty-hand” fighting like jujitsu, bladed-weapon systems like kendo (formerly kenjutsu), or stick systems such as embodied in jodo (formerly jojutsu), all of them became “fighting” systems because of kata. Under no circumstances did these great systems get strong simply by having various combatants getting in and “mixing” it. It was a normal process of “walking before running” in which efficient movements and technique was first designed, tested, improved, and finally standardized through the media of kata. Kata always preceded randori and the true combative test, the shinken shobu. Jigoro Kano, in his synthesis of Kodokan Judo from jujitsu and other combative systems, recognized this necessity and did not build his famous Judo system in a free “hammer-and-tongs” type of training. In practical terms, translated for your training, this means that unless you have technique built and working for you, you cannot hope to compete effectively on sporting contests because you will not have the proper skills. You too must learn to “walk before you run.” The difference between great champion Judoists and those who just putter around and never make it is largely due to the amount of time spent in developing tools to work with — techniques and a strong body. There is no better way of achieving this than by a balanced use of kata study as a regular supplement to training. Each technique of kata has a basic principle which, if understood and mastered in kata form, can easily be applied to variations which will broaden and strengthen Judo performance in general. It is also significant that you know that Jigoro Kano thought highly of nage and katame no kata and referred to them under the combined title of randori no kata. His insistence on this term should tell you immediately that they are inseparably linked to randori. The founder thought of these two kata as the basic foundations to every Judoist’s skill — fundamental building blocks by which a Judoist might develop his techniques as broadly as possible. He expected all Judoists to make a regular study of kata. Still another important issue about kata is that the founder did not want kata to be purely a ceremony. In all his technical notes, the underlying idea is “take the ceremony out of kata.” What this implies is that, while kata is an excellent manner by which to display or exhibit Judo, this should not become the fundamental purpose of kata. Kata properly applied belongs in the training of all Judoists; kata is a training method, a “tool,” if you will. By the founder’s thought, full Judo maturity cannot be achieved without substantial doses of kata applied throughout the Judo life of each Judoist. Kata is an intrinsic training method of Kodokan Judo, and it has two distinct developmental stages. The first of these is the “doing” stage — a time when we must study and practice it so that we can gain a mechanical understanding of it. It is a time when we are concerned with each and every technical detail. At this stage, kata is of little training value as a completed training tool; we are simply shaping this tool for later use. After we have a rather good technical basis for kata and can give a rather polished performance of it, then we can put it to use and find answers to technical problems about the various techniques it embodies. This is what can be referred to as the “using” stage. Then and only then will kata become truly useful. Each Judoist differs in his learning ability, and it is difficult to generalize about when to begin kata study and when to expect that a Judoist can attain the “using” stage. Though kata can be begun at almost any level of Judo experience, it is perhaps best started at the sankyu level; and with constant study and practice, allowing two or three years in which to complete the “doing” stage, a Judoist can, after that, put it to optimum use. Inherent in each technique of kata are “lessons” essential to an understanding of that technique, basic and variation factors which enhance the polished performance of the technique for randori and shiai. In direct practical terms for training, this means that kata can teach the reasons why a technique will succeed or fail in randori or shiai application. However, in order to be able to find those “lessons” in the kata, the Judoist must have developed his kata out of the “doing” stage into the “using” stage. That kata is a prearranged exercise is perhaps the source of the biggest misunderstanding. To most Judoists and many inexperienced instructors, this “cooperation” has come to mean that tori is always a “winner,” uke going down to a well-deserved “defeat.” It also comes to mean that uke, in his cooperation, must “jump” for tori, trying his best to make the whole performance look good. Nothing could be more erroneous or injurious to the use of kata as a training tool. To see this, let us turn back to the two developmental levels of kata, the “doing” and “using” stages discussed earlier. Kata performed as an exhibition or demonstration is largely a “doing” type of kata. By the nature of demonstration, kata used in this fashion always sees tori emerge victorious to graphically show technical aspects about Judo in informing or entertaining an audience. Uke’s cooperation here, however, must not be one of “jump” for tori, in spite of the predetermined condition of “losing” to tori. Kata, as a demonstration, is but a shallow and limited usage of kata; it is not the primary purpose of kata, though most tendencies in modern Judo restrict it to this role. But, even here, if correctly performed as the founder intended, it is a beneficial performance. Kata, performed as a “using” type of exercise, will see the failure of many attempts by tori to apply his techniques; tori will not always “win.” This is as it should be, if kata is being used correctly. The kata is thus an evaluation device with registers incorrectly applied technique and can reveal the reasons why tori is failing to produce the correct results. In nage no kata, uke makes only predetermined efforts to foil, and tori beforehand realizes these actions are to come. In spite of this knowledge, should the technique not come off well, it is a very definite sign tori is not applying his technique properly. How can he, under failure with a cooperative uke, expect to “defeat” a non-cooperative uke in randori or shiai? In katame no kata, after certain preliminaries, uke is free to actively, and in an undetermined way, extricate himself from tori’s technique. Uke’s escape actions are not prearranged, except to the extend of utilizing legitimate Judo methods. If, with this “perfect” chance to immobilize uke, tori fails, how can he ever hope to immobilize a uke who, from the beginning, is struggling to defeat him? Cooperation in kata is only a limited one which requires uke to be in a certain position at a certain time so that tori can apply the required technique. This arbitrary preparation does not include the “jumping” of uke or feeble attempts to grapple with tori. In nage no kata, uke is thrown down and thrown hard! In katame no kata, uke is held, choked, or arm-locked effectively, or uke is at liberty to escape. This is the founder’s intended “use” of kata; nothing less an interpretation has optimum value. When speaking of the prearranged nature of kata, I found something in Jigoro Kano’s technical notes which was a “bombshell” to me — at least until I thought it out. I pass it on to you. How many times have you heard a Judoist say, “kata…..nah. Never use it for training. I’m a believer in uchikomi as the best way to learn a technique”? Here’s the “bombshell”: In the founder’s mind, uchikomi is kata. Think about it. In uchikomi we have nothing more than a prearranged method of working with our uke. We repeat certain actions against his more-or-less cooperative self. We both know what is going to happen. I am rapidly exceeding the space allotted to me, and so I cannot give you much more data; but I do want to leave you with two more important aspects about kata. The first of these is that from the onset, as you study and practice kata, you must have a thorough understanding of the basic roles of tori and uke from the standpoint of who is attacking. On the surface, this sounds like a silly statement; but since the essence of the kata is here, let us take only a brief general look at it. Generally, it can be seen that uke attacks tori and by skillful, correct maneuvering, tori manages to overcome uke. This is not always the case! In nage no kata, there are certain techniques where uke only wishes to attack; he “thinks” about attacking and has the attack initiative “stolen” from him by tori. Still another, uke attacks, loses the attack initiative, regains it, and loses if finally. The technical explanation here is involved and is related to what is known as different stages or sen or “initiative”: we cannot delve into this here. I merely wish to alert you to the fact that, unless you know each and every technique from the standpoint of who attacks and defends and the interchange of attack initiative, you cannot hope to perform kata correctly. Only competent instruction can guide you here; seek it out. Finally, many Judoists complain that kata is subject to instructor interpretations, “How can I do kata when one teacher says one thing and another says something else?” The question is pertinent and so important that I want to squeeze it in here. Kodokan kata is standardized. There is a technically “right” way (only one); but you must bear in mind that, by natural evolution, Kodokan kata has changed over the years. From the founder’s time, there have been modifications — even the actual changing of techniques. In 1960, the Kodokan sought and got the agreement of all master Judoists in Japan, formulating a standard method of kata. Therefore, Judo instructors who are not up to date on this standardization may be using older concepts no longer in vogue. Other variations in teaching are usually the result of personalized versions or lack of knowledge about kata. Thus, the selection of a qualified up-to-date instructor is vital to your getting the truth about kata for your training. Along these lines, you should also know that Kodokan kata, while standardized, is not the only Judo kata existent. There have been various attempts by high-grade Judo instructors from Japan to establish private kata or interpretations of Kodokan kata. The matter becomes not so much a matter of which kata are “right” and which are “wrong” as understanding that this divergence exists. But the thing you can be sure of is that a standardized Kodokan kata exists; and if you are interested in it (and you should be), you will perhaps have to search it out from quite a variety of kata styles. Kata is vital to Judo maturation — both to the Judo as a system, and to you as an individual Judoist. It must be emphasized as a training method, not a demonstration. The truth about kata is not currently being placed before the Judoists of the world, and they have every right to label what they now see being passed off as kata, as something weak and almost useless. They are right about true kata. It is a case of the singer, not the song. PART 2: JU NO KATA So-called “Forms of Gentleness,” as the ju no kata is referred to, is a grossly misinterpreted standard of Kodokan. As performed in modern-day judo, it contributes little more than restricted and token help to judo training. I’ll begin by qualifying this statement. The Japanese ideogram ‘ju’ coincides in form and meaning with its Chinese prototype, though not taken from Chinese conceptual sources. it was merely adopted as a Chinese ideogram for phonetic purposes. ‘Ju’ denotes various meanings in the Oriental mind which, in the English language, can be approximated only by concepts including: gentleness, softness, pliancy, yielding, tractibility, submissiveness, weakness, harmoniousness, as well as a state of being at ease. All of these denotations involve philosophical complexities of absoluteness and are not relative or practical connotations. Herein lies the source of the error. The usual word selected for the international interpretation of the ideogram ‘ju’ is “gentleness.” This, however, is compounded and confused by the fact that the Japanese, including Jigoro Kano, endorsed it. But the word ‘gentleness’ had a different meaning to Jigoro Kano than it had for the westerner. Not only has the interpretations of the ju no kata been undermined, but the very principle of judo has become warped and distorted from the original Kanoian thinking. Westerners have accepted the Japanese selection of the word “gentleness” and have, arbitrarily, without familiarity or regard for the founder’s intentions, taken the word in its absolute denotation. By this absoluteness, “gentleness” has come to imply only soft, prissy, almost mamby-pamby sort of action or the “la-de-dah” type of movement which admits to no great application of muscle strength. Under this interpretation of “gentleness,” judo is all yield. To yield is esteemed, while hardness is shunned. Thus armed with this conceptual error, western Judo instructors are developing a “soft” Judo, thinking it to be in line with the founder’s ideas. Persistence in this type of thinking is doing great damage to western Judo (just as it did to jujitsu in Japan) and is certainly not in concept with the intention of the founder, Jigoro Kano, who always took exception to the abstract philosophical view and insisted on the narrower, but relative and practical outlook. There is a large amount of documentation to support the Kanoian thought; but somehow it isn’t being seen, or if it is, it is not being correctly read or understood. In Jigoro Kano’s own writings we find:

Such is the principle of ju. But, strictly speaking, real Jujutsu (Judo) is something more. The way of gaining victory over an opponent by Jujutsu (Judo) is not confined to gaining victory only by giving way. Here it is evident that the founder did not consider “gentleness” to be “softness” or “yielding” as the entire makeup of the principle of Judo. He indicates that still another facet is inherent, by continuing:

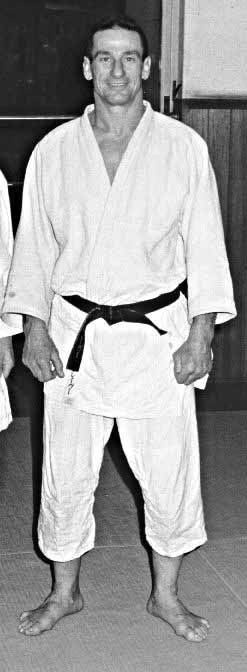

It is now clear that the founder recognized the necessity of using strength to overcome some forms of resistance and included resistance itself within the principle of Judo. It is not the factor of strength that Dr. Kano opposed, but its misuse. Ju, in the principle of Judo, stresses flexibility in change or the adapting to any situation and economizing mental and physical energies Perhaps a better interpretation of ju would have been “flexible” or “flexibility”; although these too, tend to narrow the tone. Yet, they seem to approach more closely the founder’s idea of ju. The ju no kata is an exercise making use of the practical interpretation of “gentleness” — not its idealistic, absolute, and impractical meaning which most westerners attribute to it. As a kata, it is really not “gentle” at all. In the absolute sense. As a properly performed exercise, it is a smooth, efficient application of mental and physical strengths, a harmony of movement combining hardness and softness in economic balance, making the kata completely functional. In this kata there are moments of yielding and resisting in both roles of tori and uke; never is there a yielding action solely. This fact provides an interesting test to its effect on Judoists who think it a useless exercise. If any well-conditioned Judoist will perform this kata correctly with a master performer, first as uke then as tori, he will find that no matter how well conditioned he may be, this kata will cause him to be covered with perspiration; his body muscles will “scream” in protest under the contractions and extensions imposed on them. To permit him to take each situation correctly, he would experience the actual moments of “softness” and “hardness” and the necessity for flexibility, both mental and physical. He would come away from this experience with a new and deep respect for ju no kata. Figure 1. shows a correctly executed ukigoshi movement of the kata as its moment of climax. Compare its technical correctness of almost hyper-extended legs, lowered head, and flattened back with a pronounced lean to the right side, to the same movement being incorrectly performed in Figures 2 and 3. Those Judoists unfamiliar with correct ju no kata technique might arbitrarily approve of the form in Figures 2 and 3. However, this form is filled with technical errors. Primarily, it is incorrect because the knees remain bent. They have not been fully extended. The upper body of tori is inclining instead of declining and has no lean to the right. Tori’s head is being dropped. This fact tends to round or hump the back, and make it impossible to “table” for uke’s use. Only a very skillful uke shown in these photos would have been able to salvage some exercise benefit for herself. Tori gets no real exercise benefit from the form shown, and perhaps comes away discouraged with the whole thing. Today’s concept that ju not kata is not functional and that it is fit only for girls’ training as a dance or game is entirely wrong. Speaking with Professor Aida, the leading Kodokan authority on ju no kata, I found that the Professor had learned directly from Jigoro Kano. He proved to be a wealth of information. While ju no kata may be ideally adapted to women’s training, it was not the founder’s idea to restrict this kata to the women’s dojo. In order to understand this better, let us take a brief but important look into the historical foundation of Judo. In developing his Kodokan Judo system, Jigoro Kano was aware that a still older judo system existed, the Jikishin school. It represented a practical approach to combative exercises by being a synthesis of jujutsu systems. In one sense, it was a challenge to the Kodokan system. However, with jujutsu on the decline in the Meiji Period (1868 – 1912), anything similar in nature had little chance of survival. Professor Kano thus labored under terrific handicaps in bringing about a national interest and governmental recognition for his Kodokan system. By his tremendous foresight and his experience as an educator, he knew that unless his Judo system could obtain official governmental sanction, it too, was doomed along with jujutsu systems. To achieve this sanction, he appealed to the Ministry of Education. Before he could do this, however, he had to show that Kodokan Judo differed from jujutsu as an educative entity in accord with the modern democratic society. One of the ways by which Professor Kano obtained approval for Kodokan Judo was through the ju no kata. It helped bring Judo into the educative sphere and meet the requirements and criteria characteristic of modern society’s educational needs. When properly performed, ju no kata gives a balanced exercise for the whole body. Constant use of this kata over an extended time period results in a harmoniously developed, flexible, and strong body, as well as giving the user the fundamental mechanics for sport and self defense Judo applications. Professor Kano’s original idea was for all Judoists, regardless of age or sex, to study and practice ju no kata. Ideally, it was to begin at an early age. Through constant practice, sound bodies could develop which might otherwise be less harmoniously developed by randori alone. Ju no kata was to be continued during adult training too, but with lesser need for body development. The higher skill of the adults with this kata permitted them to study applications of Judo mechanics and self-defense. A Judoist who might start late in life would be given ju no kata practice in order to bring his body condition to a more suitable level for randori. The tendency to let girls “take over” ju no kata has, in the opinion of many Judo experts, seriously weakened its intrinsic values. This parallels one other such case in Japanese martial arts history. Originally, the naginata, a long halberd-type of bladed weapon, was a formidable weapon in combat. It remained in male samurai hands until the Tokugawa Period (1614 – 1867). As an effective weapon requiring perhaps the least amount of physical strength to make it combatively effective, the weapon was given to samurai women as their combative “baby.” Their consequent development of it has brought the naginata jutsu to today’s level of combative degeneration, and it has become largely an aesthetic practice. The nature of women making physical exercise beautiful, graceful, and the like, is similarly affecting the Kodokan ju no kata. even in Japan it has deservedly gained the appellation of odori no kata, or “dance forms,” and is the subject of ridicule by most young male Judoists who have never had sufficient experience to realize that this is not true ju no kata. It is another case of the singer, not the song. The ju no kata of today can qualify only as a moderately good exercise, but it falls far short of the original Kanoian form. If efforts were to be made to recover the original form and if Judoists were to study and practice this kata as part of their normal training, all would benefit. Apparently, the limiting factor is the inability to find instructors who know and are able to teach the original form. Until this adjustment is made, Judoists will go on referring to it as “useless” and a waste of training time, and something which should be restricted to female trainees. Judo instructors charged with placing and maintaining Kodokan Judo within educational institutions should realize that unless ju no kata is included as a regular part of Judo training, Judo is narrowed. It will not meet the criteria required of the Principle of Judo applied to self-defense situations; and unless the instructors are qualified through experience with this kata, he cannot hope to understand these elements. Nor can he teach this kata properly. The present day deficiencies in applying this kata to training can only be remedied by instructors who take the initiative to restore the Kano form.  While the old form, jujutsu, was studied solely for fighting purposes, Kano’s new system is found to promote the mental as well as the physical faculties. While the old schools taught nothing but practice, the modern Judo gives the theoretical explanation of the doctrine, at the same time giving the practical a no less important place. …..T. Shidachi, 1892 |