I believe I can roughly divide my career as a judoist into three periods. The first period sees me entering Riichiro Watanabe-sensei's dojo in the city of Yokosuka, still a boy and intent on becoming a strong judoist. The second period includes my first participation in the All-Japan Judo Tournament. I broke the jinx that said a newcomer would never win the tournament, and in so doing also established a important record as the youngest man ever to win the title of judo champion of Japan. This second period also includes my winning the heavyweight-class judo championship in the 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games and the open-division title in the Fourth World Judo Tournament in 1965. The third period covers the days up to the present and my work as an instructor developing promising young judoists. In each of these three periods I have concentrated all of my efforts and enthusiasm on judo. But when I was a child I was rather sickly and did not have much of a physique. Also, I was not very agile or dexterous. The only weapon I had at my disposal, then, was a fighting spirit-a spirit which gave me the confidence that I would not be defeated by anyone. And I think it fair to say that it is this fighting spirit which 100 k characterized my judo throughout my career. I had good ippon seoi nage and tai otoshi but it was because of my fighting spirit that these techniques proved effective against my opponents. As a boy, as an active judoist, and as an instructor, I have experienced a great many things, all of which I can hardly relate here. Based on my experiences. however, I will jot down some of my observations about judo. Never Give UpJudo is a combative sport. It is a martial art aimed at defeating your opponent. Other purposes of judo involve developing physical strength and mental spirit. But when you are up against an opponent, you must never forget the combative aspect of the sport. You fight against your opponent, throwing him down to the mat to achieve victory. At the same time, you fight against yourself. If you think your opponent is stronger than you and get the jitters, or if you are in a difficult position and feel that you must give up, then it will be impossible for you to win. You must not give up the bout until the last second, no matter how strong your opponent may be. You must have a fighting spirit which will urge you on to attack and attack again to the very end. Fighting spirit, to put it simply, is the first thing a judoist needs. Of course, I cannot deny that you may feel anxiety or uneasiness before a fight. Feelings like "I don't want to be beaten," "I just want to run away," or "I'm frightened" are always felt to a certain degree. Also there is loneliness. But what is important during these times is not to be afraid of loneliness, anxiety, or weakness of the will but to overwhelm these feelings with a fierce fighting spirit and confront your opponent with your intention to defeat him. I experienced such anxiety and overcame it when I participated in my first All-Japan Judo Tournament. It was 1959. I was a senior at Tokyo University of Education and was unknown as a judoist. Furthermore, I was the smallest man in the tournament, weighing only 83 kilograms and standing 173 centimeters tall. As I mentioned, there was a belief that no newcomer could ever win the tournament. My opponent in my first preliminary bout was Yuzo Oda, a giant of a man — 193 centimeters tall and weighing 100 kilograms. Because Oda had been touted as a sure winner of the tournament, no one believed I had any chance of beating him. Before I fought Oda I was deep in thought for a long time. After considering it over and over, I decided that the best strategy would be to launch an attack against Oda time and time again, relentlessly. My idea was to "do or die": and I hoped to discover a way to win by hammering away on the offensive, as is suggested in the old Japanese saying, "Attacking is the best defense." In order to carry out this strategy it was necessary for me to have the stamina to continue my attacks, as well as the fighting spirit that would enable me to generate such stamina. By nature, I disliked being beaten by the other fellow, and since I had built up my stamina during practice sessions, I attacked Oda without fear. As a result, my strategy proved successful, and after fighting for the full time I won the bout with yusei gachi (judge’s decision). This was a very important victory for me and signified the first step toward the maturation of my judo. Also, from this victory, my confidence increased considerably in regard to my notion that one must always go on the offensive in judo. After winning my first bout with Oda, I won all my other matches up to the finals. And by defeating my opponent in the finals my confidence in my judo increased even more. My opponent here was Akio Kaminaga another man thought to have a held a good chance of winning the tournament. He, too, had won all of his matches up to the finals. By the time of my bout with Kaminaga, all of my stamina was depleted and I was resting in a very exhausted state in the dressing room, muttering words to the effect In that I couldn't possibly win. Hearing these words, Watanabe-sensei scolded me time sharply. Encouraged by his scolding. I went up to the judo arena. My match with Kaminaga proceeded with him in a superior position, but about one minute before the end the big clock in the arena caught my eye as I returned to the mat. I thought to myself. I must beat him with my favorite ippon seoi nage before the time is up. As soon as I grabbed hold of Kaminaga. I pushed him backward to get bled him into position. Up to then, Kaminaga had thwarted all such attempts of mine. But this time, when I pushed him backward, he moved forward together with my push; taking advantage of this, I made the throw. The hall was in an uproar, and after several moments the chief referee declared my seoi nage a waza ari (half point) Thus I had managed to come from behind to win the title of the All-Japan Judo Tournament. My victory was the result of my never giving up the match until the very end. There are some judoists who are quite strong during practice sessions but who fail to live up to their expectations in competition. There are also judoists who in a match are unable to execute the techniques that they are actually in full possession of. The problems here lie in the attitudes of these men before the fights begin: They defeat themselves before they enter the judo arena. Only by using all your energy and spirit until the very last can you win a bout. I become more certain of this each time I watch Yasuhiro Yamashita. Yamashita is one of my protege’s. He is also the one who broke my record as the youngest judoist to win the All-Japan Judo Tournament. Yamashita is not only a big man, but also a fighter who likes to train very hard. During the Jigoro Kano Cup International Judo Tournament held at the Nippon Budokan (Tokyo) in November 1978, Yamashita exhibited fully a fighting spirit that simply overwhelmed his opponents on his way to winning the open-class title. The open-class bouts were held on the fourth and last day of the tournament. Aside from Yamashita, those participating were Novikov of the Soviet Union, winner of the open-class title in the Montreal Olympics, Rouge (France), Adler (the Netherlands), and other top-flight judoists of the world. In his second bout, Yamashita met the big Russian Turin. Yamashita had a hard time getting his techniques to work because Turin continued to take strong defensive positions. Yamashita was taken for a koka (two steps below a waza ari) when Turin countered with a technique after Yamashita had attacked. The spectators in the hall gasped when the koka was proclaimed and everyone thought that the seemingly invincible Yamashita would go down to defeat. But Yamashita redoubled his attacks against Turin, who maintained his defense with his long arms. Several seconds before the match was over, Yamashita unleashed o-uchi gari to pick up a yuko (between koka and waza ari) and a victory. During the finals, Yamashita met Rouge of France, and although the techniques of the two men were ineffective, it was clear that Yamashita was the more aggressive and that the bout was in his favor. Yet Yamashita continued his relentless attack against Rouge and just before the end of the match he caught him with o-soto gari to gain a yuko and the title as well. It was a brilliant strategy on the part of Yamashita. The spirit of a combative sport is that one does not give up until the very end and keeps up a relentless attack against the opponent. Always take a bold, forward posture and sweep away your fears. No matter what the situation may be, as long as you have a fighting spirit and the desire to win you will always discover a way to won to victory. Build Up Your Body and Your Techniques

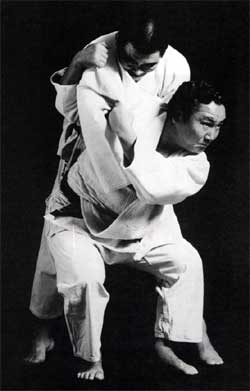

I have often noted when viewing international judo tournaments in recent years that Japanese judoists are inferior to their foreign counterparts in basic physical powers and, as a result, lose their bouts without being able to apply their techniques to the fullest. There is a saying which gets to the heart of judo: Ju yoku go o seisu (Softness overcomes hardness). There are some who, hearing this, believe that even without strength they can defeat their opponents. But this is false. How can a man who has not trained diligently or who has not built up his physical strength defeat his opponent? Adages like "Softness overcomes hardness" or "A small man can defeat a big man" only apply when your basic physical powers are on a par with the opponent's; in such a situation, power is not the issue, and it is here that we first glimpse the importance of the smooth working of shin-gi-tai in a match. It is my opinion that the techniques of Japanese judoists today are more varied and on a higher level than those of their foreign counterparts. But in order for these techniques to be truly effective, Japanese judoists have to develop basic physical powers that are in no way inferior to anyone else's. Many foreign judoists on the scene today possess not only excellent basic physical powers but also strong techniques that have overwhelmed their Japanese will opponents time and time again. Among the foreign judoists with brilliant shin-gi-tai are the Soviet Union's Nevzorov, the victor in the light-middleweight class in the Montreal Olympics, Dvoinikov of the Soviet Union, who was runner-up in the middleweight division at the same Olympics, and Lorentz of East Germany, who won the 95-kilograms-and-under class in the Jigoro Kano Cup International Judo Tournament held in Tokyo in 1978. Because I was small physically, I took up weight training during my boyhood in order to overcome this handicap and strengthen my body. With my new power, and in combination with my favorite technique seoi nage and tai otoshi – I built up my own judo. I believe that a small man like me was able to beat bigger men because I was able to back up my favorite techniques with basic physical power. A judoist's strongest and best techniques become his weapons during a contest. Being strong, the more authority in their execution the more effective the result. But it takes a long time and some very hard practice to develop techniques that you can truly call your own. My favorite techniques were seoi nage and tai otoshi. Both involve heaving up the opponent from below. I learned them from Watanabe-sensei, who often used to tell me that if a small man is to defeat a big man, the small man must practice and master katsugiwaza, or carrying techniques. I was never one for exhibiting brilliant judo techniques. But as far as my ippon seoi nage was concerned, I was always sure I could bring down my opponent, no matter who he was or what the situation, as long as I caught him in exactly the position I wanted him. Power, speed, and stamina are going to be particularly important in judo from now on. Becoming able to win a judo match will involve adding basic physical training to your daily practice to develop these qualities as well as working to master techniques of devastating effectiveness. Don't Stop Learning |

|

I started learning judo at the age of fifteen, intent on becoming another Sanshiro Sugata, the great master of judo who has been depicted in Japanese novels and movies and on television. Since then, I have spent my life involved in judo and have learned many lessons from the sport.

I started learning judo at the age of fifteen, intent on becoming another Sanshiro Sugata, the great master of judo who has been depicted in Japanese novels and movies and on television. Since then, I have spent my life involved in judo and have learned many lessons from the sport. You may have fighting spirit, but if you don't combine it with excellent techniques and in you can't win a bout. It is often said that shin-gi-tai (spirit, skill, and power) is necessary to win in judo. You have to train hard so that these three elements will be in harmony with each other when you face your opponent in the judo arena. Hard training will not only dispose of your anxieties, but it will also create physical strength and fighting spirit, thus enabling you to fight with everything you have.

You may have fighting spirit, but if you don't combine it with excellent techniques and in you can't win a bout. It is often said that shin-gi-tai (spirit, skill, and power) is necessary to win in judo. You have to train hard so that these three elements will be in harmony with each other when you face your opponent in the judo arena. Hard training will not only dispose of your anxieties, but it will also create physical strength and fighting spirit, thus enabling you to fight with everything you have.