by Harold (Hal) E. Sharp

I would like to share some of my experiences with you about my Sensei and dear friend, Takahiko Ishikawa, 9th Dan, who passed away at the age of 91 in June, 2008. I first met Ishikawa in 1953 in Japan after I became a Shodan (1st degree black belt) and thus was allowed to workout at the Keishicho (Tokyo Police Dojo). At that time Ishikawa had a favorite student, an Englishman by the name of Malcolm Gregory, who helped me improve my judo skills and introduced me to Ishikawa. Background:Ishikawa was the All-Japan Champion in 1949 and 1950. The 1949 championship final was against Kimura. The head referee was Mifune, 10th Dan. The match was a draw (hikiwake) thus an extension was granted. Usually in such an important contest two (2) extensions may be granted before a final decision. However, in this case the first extension ended in a draw and a second extension was not granted. Mifune declared both Ishikawa and Kimura as Champions of Japan. After that match Kimura left judo to enter professional judo and wrestling. Ishikawa won the championship in 1950, lost in 1951, and retired from competition. He was the youngest person to be awarded the title of Shihan (Professor) at the Keishicho. 1953: This was a big year for the Sensei and me. I was awarded Shodan rank (1st degree black belt) and the book, “The Sport of Judo”, which I co-authored with Kobayashi was published. Also, Ishikawa became part of a team of outstanding instructors which toured the United States under sponsorship of the U.S. Air Force. The team included S. Kotani, T. Otaki, C. Sato, T. Ishikawa and Kobayashi for Judo and K. Hosokawa, K. Tomiki, for Aikido and Self-Defense, and I. Obata, T. Kamata, H. Nishiyama for Karate. 1955: This year I was promoted to Sandan rank (3rd degree black belt). By now I had a reputation as a writer of judo books, therefore, Senseis Takagaki, Ishikawa and Mifune asked for my assistance with their books. Takagaki and I wrote “The Techniques of Judo”. Ishikawa asked me to write the technical descriptions for photographs used in his book. Mifune wanted me to edit his English version of the “Canon of Judo”. Working on the book with Ishikawa led to many hours of discussions where Sensei told me his life story and his thoughts on competitive judo and how to be a champion which will be discussed later in this article. Ishikawa’s book was never published because he left Japan for Cuba. Many years later Mrs. Helen Foos published a series of Ishikawa Journals which contained parts of his unpublished book.

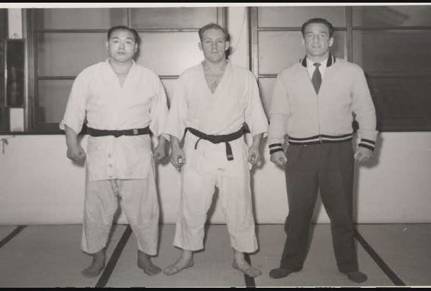

The War Years:Japan was at war from 1937 to 1945. Military training was mandatory in Japanese schools and the students’ military records followed from school to military service. Ishikawa was his high school judo champion and he had to represent his school in an important tournament. Unfortunately the tournament and a school examination were scheduled for the same time. Ishikawa requested that he be excused from the examination so he could compete in the judo tournament. The school military officer refused his request. Ishikawa disobeyed the officer and competed. As a result a black mark was entered into his military record. Normally Ishikawa would have qualified to be an officer as other members of his family were. Instead Ishikawa became an enlisted man and drove a truck in Manchuria. During the war the United States fire bombed Tokyo which resulted in the destruction of his records. Ishikawa told me it was ironic because if he had become an officer he might have died in the Pacific Battles like his relatives. Since his military records were destroyed he was able get a great job with the Tokyo Police as a judo instructor. How To Become A Judo Champion:After discussing specific techniques illustrated in his book, Ishikawa would speak his thoughts on becoming a champion. In this writing I will only address some of the key points. Ishikawa spoke of the importance of the mind, posture, control and training. All of these subjects are interrelated. We often receive constructive suggestions from judo teachers, however, we normally do not follow these suggestions. Most players tend to practice their favorite techniques (Tokui Waza) and train the same way. Ishikawa’s influence caused me to change my approach to judo. By following his suggestions my power, mentally and physically, seemed to double. I rarely was thrown. I became very positive and aggressive and stopped defensive actions. I learned to take advantage of my opponent’s movements. I stopped trying to force my favorite techniques on my opponent, instead I attacked based on the opportunity my opponent gave me. The Use of The Mind:Ishikawa considered this to be the most important factor in becoming a champion. When Ishikawa was a young judoka he would prepare himself before a contest by repeating over and over “I am going to win”, “I am going to win”. Then he would mentally plan the techniques he would use, like Osoto Gari and Ouchi Gari, then repeat this over and over in his mind. Later in his career he fought more by taking advantage of his opponent’s actions rather than force his favorite techniques. He related the ultimate power of his mind when during the 1949 All-Japan Championship he was seriously injured and became unconscious. His opponent, Daigo, attempted a powerful inner thigh sweep (Uchimata) which crushed one of his testicles. When Ishikawa was revived he continued to fight and beat Daigo. In spite of the intense pain he went on to fight Kimura, the toughest competitor in Japan. As previously described the main bout and first extension ended in a draw. The head referee, Mifune 10th Dan, decided not to have a second extension and thus declared both players as champions. Ishikawa told me he was disappointed in not having a second extension because he was certain that he could defeat Kimura. After they bowed out Ishikawa collapsed and was taken to the hospital. During our discussions I asked Ishikawa if he ever practiced hand stands to escape from throws. He said, “I use to practice hand stands but then I thought this is training to lose. I will not lose. Of course if someone tries to throw me I can avoid being thrown”. His lesson was do not train to lose, only think of winning. Ishikawa’s Sensei, Sone, was an ardent believer in the power of the mind. One day Sone introduced Ishikawa to a Living Kamisama (God) on the outskirts of Tokyo. The Kamisama had displayed unique powers over his disciples. Ishikawa described the strange behaviors of the disciples and invited Nishiyama, a Karate Instructor, and me to join him in a visit to the Kamisama. When we arrived at the Kamisama’s house, we were ushered into the main room. The Kamisama was wearing a black Hakama and sat on a raised dais. His disciples sat in a row before him in a zarei position with their hands pressed together and held up as if meditating or praying. The three of us assumed the same position along side the disciples. Although I was to meditate I couldn’t help but peek at the disciples. Disciple One started to vibrate and twisted on the mat like a pretzel. Disciple Two would swing his arms to and fro, and with every other swing would pound his tummy. Disciple Three shook and cried. He later told us he saw a gold image of Buddha. One by one, the Kamisama had each of us sit in front of him. The Kamisama blew air across our forehead. He then dismissed us. We bowed and departed. We had tea with the disciples and each one explained their experiences and how this helped them. When we walked away from the house Ishikawa asked Nishiyama if something happened to him. Nishiyama said no. Ishikawa then asked me and I shrugged and said no. Then I asked him if he experienced anything and he responded no. But Sensei I replied, “you did a beautiful Tanko Bushi (coal miner’s dance)”. Ishikawa was stunned and asked Nishiyama, “honto (truly)”. I winked at Nishiyama and he replied, ”honto”. Nishiyama could not keep a straight face and cracked up and tried to punch out a telephone poll. Posture and Form:Ishikawa suggested that you stand straight bending slightly forward like a boxer, arms in front of you at a ninety degree angle. Your hands and wrists should be turned outward so that the heel of your hand is forward and your elbows are near your side. Although you grip the opponent’s judo gi with your hands you should keep your mind in your elbows so that you push, pull or lift with your elbows. This makes your actions more of a body movement not just a hand action. This method makes you stronger and avoids telegraphing your actions. Pushing or driving is done with the heel of your hands versus the knuckles. Move on the balls of your feet, gripping the mat with your toes when you throw. Balance and Control:Ishikawa believed that if you become part of the opponent’s body, as one, it is easier to anticipate his actions and to respond automatically with a block or throw. Also, lean slightly against your opponent creating a downward vector or line of power from your elbows to his center of gravity which is a point behind his navel. To develop your confidence, try this while blindfolded and have your opponent really try to throw you. Ishikawa theorized that when an opponent attempts a forward throw, the opponent will have the advantage if he can turn his back into your chest. Therefore, if you strongly pull his opposite side it will stop his rotation. This action will press the opponent’s side into your chest. For example, if both men are in a right side position and your right hand has a lapel or pocket grip on his left side, then as he rotates pull hard with your right hand crushing his right side into your chest. At this point you can throw using a turnover throw or other throws like Ushiro Goshi and Utsuri Goshi. Ishikawa was credited with developing this turnover move where as you snap the opponent into your chest you squat and hook his right leg from behind with your left arm, lifting with your legs and pulling his left shoulder down in a circle, and throwing the opponent on his back. Ishikawa said there was no name for this throw, although some incorrectly called it Teguruma. Since we were writing a book I made up a Japanese name for the throw. Ishikawa was shocked and said do not say that because it is a bad word in Japanese. Since then The Kodokan has recognized the throw and classified it as a Sukuinage. Training:Ishikawa suggested that for every hour you train at the dojo with others you should train two hours by yourself. Because of my work schedule and judo practice I was only able to devote one hour each night to self training. I used a bungee cord to practice throws and did shadow throwing, newaza drills, squats, push-ups and sit-ups. The effect of this routine seemed to doubled my power and improved my reflexes. In Japan most of the time in the dojo was dedicated to randori with little or no training routines. Ishikawa In Cuba:In late 1953 the Cuban Judo Association requested an instructor from the Kodokan to train their judoka in competition skills. Ishikawa was selected because he was a two time All -Japan Judo Champion. When he arrived in Cuba he worked softly with the Black Belt Students and he let them throw him. The President of the Cuban Judo Association wrote a letter to the Kodokan stating that he was disappointed in Ishikawa and that students were throwing him with ease. The Kodokan sent a copy of this letter to Ishikawa for his information. Ishikawa became angry and had his good friend and student, Malcolm Gregory, fly to Cuba. When Gregory arrived Ishikawa showed him the letter, gave him a judo gi and took him to the dojo. Ishikawa had all the Cuban Black Belts lined up for a slaughter line. He told Gregory to start at one end while he would start at the other end. Gregory told me that he was out of condition, so when he saw how fast Ishikawa was throwing the Cubans he slowed down and let Ishikawa do most of the work. After that session the Cuban Judo Association President became embarrassed, apologized and asked Gregory what he could do? Gregory replied, “write another letter”. As a side light I would like to share a funny story that happened when Gregory lived and trained with the Sensei. Because of the hard training Gregory cherished every moment of his sleep. However, early every morning Grandma would clean house using a duster to slap the Shoji Doors. Gregory complained to Sensei that the noise woke him up and he needed his sleep. He pleaded with Sensei to ask Grandma not to clean with the duster so early in the morning. Apparently Sensei did not get the word to Grandma for she kept banging away each morning. Gregory loved to sing grand opera and owned a record player. One morning after Grandma awakened Gregory, he cranked up his player and as loud as he could he sang along with the record. Everyone in the house and nearby houses jumped up and complained about Gregory’s noise. Ishikawa shouted, “Gregory, are you crazy”? Gregory responded, “When I cannot sleep I must sing”. Grandma got the message and stopped early morning cleaning. In the photo below Grandma is standing in front of me.

Ishikawa In The U.S.A.:I lost all contact with Ishikawa after he left Japan for Cuba. From Cuba he moved to the United States under the sponsorship of Mrs. Helen Foos of Philadelphia. Sometime in the 1970’s I was given a box of over three hundred photographs from the book we had worked on. It was like a giant jig saw puzzle, but I was able to put them in order by technique. I returned them to Mrs. Foos who used them in the Ishikawa Journal that she published. Later I visited Sensei in Philadelphia in an attempt to finish the book. We took a few fill in photos with me as the uke. Then I asked Sensei to show some escapes from chokes. He shouted at me that when he chokes no one escapes. I explained that this was just for the book, so he agreed to show some basic escapes. Then I asked him to show some escapes from arm locks. He shouted again at me that when he does arm locks no one escapes. Again I pleaded that this was only for the book and so he showed some basic escapes. Many years later, in the 1980’s, I visited Ishikawa and Mrs. Foos at Virginia Beach, Virginia where she had built him a beautiful dojo. This is where I learned of his great passion for GO, a Chinese chess game played with black and white stones. Apparently Ishikawa was the second highest rated person in GO in the United States. On Sundays he played the number one player by telephone. During my visit we could not stop talking about the old days in Japan and our judo friends. He was concerned about the judo political problems in the United States. Ishikawa felt the biggest problem was the awarding of high black belt ranks. He recommended that rank should be limited to Godan (5th degree black belt) and that certificates be awarded for different levels of teachers. When Ishikawa drove me to the airport he confided that the death of his son Hajime, tore his heart. He longed to return to Japan and be buried near his son. Hajime had died a tragic death when he was a teenager. I tried to console him by saying that he did so much to help his students. He said he understood but that the death of a son is especially difficult for a Japanese father. I told him how he affected my life and judo. My heart and mind doubled in power. There was silence and then he said, “I understand, but if you use that power for evil you will lose it”. With that our discussion ended. I thought this was like a Star Wars movie script. I did not see him again until May 2007 when I visited him in Japan with his second wife Aiko. Ishikawa apparently had a stroke. He could not speak or feed himself. I showed him a video on my laptop computer of him doing judo in 1953 in Japan. He perked up and intently watched the film. This brought his wife to tears. She thanked me. This was the last time I saw him. I plan to finish a DVD film of Ishikawa, Daigo and other champions from the 1950’s in the near future. Please forgive any ramblings and errors in this article since I am 81 years old and tend to have senior moments. |

|